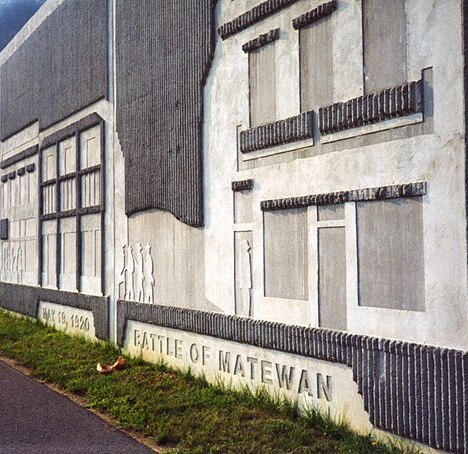

Prof. Green says she wanted her students to hear a first-hand account of how memories can grow powerful enough to shatter the silence. To do so, she took her students on a field trip to the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, which is about a four-hour drive from W&L’s campus in Lexington, Va.

Prof. Green says she wanted her students to hear a first-hand account of how memories can grow powerful enough to shatter the silence. To do so, she took her students on a field trip to the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, which is about a four-hour drive from W&L’s campus in Lexington, Va.

The decade-long Mine Wars began in 1911, when coal miners in West Virginia began demanding better working conditions. They wanted a 40-hour work week instead of a schedule determined by how many pounds of coal they could dig. They sought safer working conditions to protect them from explosions and mine shaft collapses. They asked to be paid in real money instead of “scrip,” which they could only use in mine company stores, where they were forced to buy food, clothing, and the equipment they needed to dig coal. Significantly, the miners wanted the right to unionize and to become part of the United Mine Workers of America.

But the powerful coal companies and local politicians they controlled rejected the miners’ demands.

In response, over 10,000 natives of Appalachia joined forces with African Americans and immigrants from Italy and Hungary to fight at Blair Mountain in 1921, making it the largest armed uprising in the United States since the Civil War.

Machine guns were attached to the tops of trains and fired into the town of Matewan to intimidate strikers and protect the strikebreakers, or scabs as they were called, who were brought to work in place of the striking miners. Bullet holes, some with bullets still buried in the brick, can be seen today in the sides of buildings that face the railroad tracks in Matewan.

Bobby Starnes, a member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum board, says the story of the Mine Wars “was only kept alive around kitchen tables and on front porches” because local politicians and coal operators “actively worked hard to prevent this story from being told.”

“The absence of the Mine Wars and other industrial abuses of power in public discourse and classroom curriculum was no mere oversight but, rather, a deliberate coverup by state officials,” according to an exhibit in the museum. During the Great Depression, the governor threatened to thwart New Deal programs in West Virginia unless discussion of the Mine Wars was removed from federally funded state history books.

Wilma Steele, one of the museum’s founders, says she would have never found out about her hometown’s history unless she had conducted her own research.

Back in the classroom in Lexington, Prof. Green’s students connected their trip to Matewan with the plight of the Mayan people in Guatemala. Like the coal miners in West Virginia, the Mayans were exploited by corporate interests. Descendants of Spanish colonizers pushed Mayan people off their land and on to fincas, which were farms meant for growing cash crops to sell in international markets. On the fincas, indigenous people were forced to work long hours in unsafe conditions, and like the West Virginia miners, they were paid in scrip, which could only be spent in company stores.

In a civil war that broke out in 1960, left-wing guerilla groups battled government military forces to overthrow the autocratic rule of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes. In the 1970s, Mayan people began participating in the fight, demanding greater inclusion and recognition of their language and culture in the country.

The 36-year long conflict was characterized by abductions and violence, and over 200,000 Guatemalans were killed or went missing. Eighty-three percent of the victims killed in the war were Mayan, according to The Center for Justice and Accountability, a nonprofit foundation based in San Francisco that seeks to bring human rights abusers to justice.

One indigenous woman, Rigoberta Menchú, helped her community resist erasure by dictating her story to an interviewer. The autobiography, “I, Rigoberta Menchú,” published in 1983, is a testimonial of her first 23 years of life. It also documents the atrocities that her family and others with indigenous ancestry endured during the civil war.

During the 1950s, the Nueva Canción (New Song) Movement swept through Chile as singer and songwriter Violeta Parra revitalized traditional folk music. At the time, the country was undergoing the processes of urbanization and modernization, and rural poor Chileans felt ignored and left behind.

One of Parra’s songs, “Arriba Quemando el Sol” (which means And Above, the Sun is Burning in English), depicts the daily struggles of the working class in a poor mining town in Chile.

“When I saw the miners inside their rooms I told myself: I think the snail has better living quarters

Or in the shadows of the law, the refined thief

While above, the sun kept burning

The rows of the small shanty homes, one in front of the other, yes, sir

The line of women, one in front of the other each with a bucket using the only washing basin

While above, the sun keeps burning”

—Violeta Parra, translation from “Arriba Quemando el Sol”

Another song, “Yo Canto a la Diferencia” (which means I Sing With A Difference in English) reflects how indigenous people had to grapple with their hatred toward colonizers while still maintaining a love for their homeland.

Students made connections between Parra’s “Arauco Tiene una Pena” (which means Arauco is Filled with Sadness in English) and their previous lessons on the erasure of the Mapuche people of Chile.

“Arauco is filled with sadness

And I cannot keep silent

This is the injustice carried out through centuries

Which have been openly seen and

Yet! Nobody has tried to change

Being able to do so! Rise up!”

—Violetta Parra, translation from “Arauco Tiene una Pena”