Professor Romina Green Rioja challenged her students to think about how history is created. She pushed them to consider what happens when history’s victors wield power over not only what is documented, taught and remembered, but also what is erased.

Some students in Green’s class were first-year students, like Clark, who were just starting their journeys at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va. Others were seniors who were finishing their history majors and preparing for graduation.

Throughout the 12-week winter term in 2023, the history students gained a deeper understanding of how people in power can influence how stories are told.

Green gave her students a foundation for understanding how and why the victors’ version of history has prevailed by introducing them to an influential book that shaped the academic study of historical memory.

“The main theoretical reading for the course, actually the first main book that we read, is ‘Silencing the Past’ by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, which is about the Haitian Revolution and the silencing of the Haitian Revolution,” she said in an interview. “Since that book has been printed in the 1990s, it has been reprinted and re-looked at. I thought it was a good way to open the discussions about the histories of colonialism, the erasure of the Haitian Revolution.”

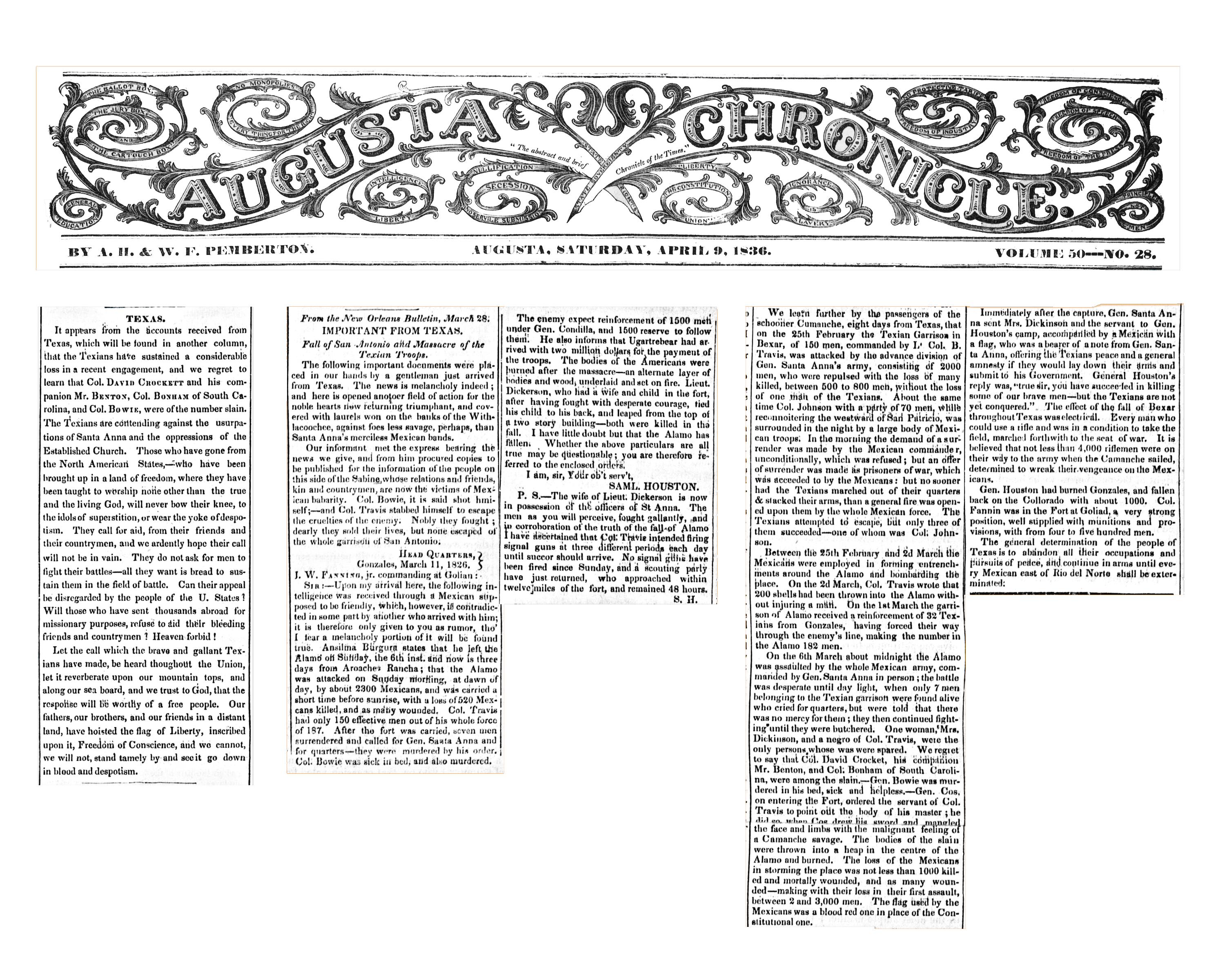

The Alamo Cenotaph Angel is part of a monument in San Antonio, Texas, commemorating the Battle of the Alamo. Source: Batlise, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Historians often describe the Haitian Revolution as the most successful slave rebellion in world history. The French had colonized the island, calling it Saint-Domingue, before the enslaved people fought back for 13 years and won their independence in 1804. The victory resulted in the establishment of Haiti, the first independent Black state in the Western Hemisphere.

The French leaders who colonized Haiti believed that enslaved black people were inferior to white Europeans. Trouillot wrote that the French, as a result, viewed their loss in Haiti as “unthinkable.”

The once-enslaved people of the island won the revolution, but they lost control of their story because French historians used their global influence to craft the narrative that the rest of the world accepted as real—as Haitian history.

Prof. Green says she recognized that students studying in the United States often find it easier to understand historical memory through the study of a quintessential story of a so-called American victory. She says that’s why she included Trouillot’s analysis of the Battle of the Alamo.

White settlers in what is modern-day Texas fought to secede from Mexico and form a republic in the 1830s. About 200 Texans made their stand at the Alamo, a former mission that was repurposed as a fort, in what is now San Antonio. A Mexican force comprised of at least 2,000 soldiers and led by General Antonio López de Santa Ana began a siege of the fort in 1836. Santa Anna’s troops defeated the Texans after 13 days of fighting.

But the Texans seized control of the narrative with “Remember the Alamo” as their battle cry.

Texans eventually achieved independence when they won the Battle of San Jacinto about a month after the fighting at the Alamo. Independence and the United States’ annexation of Texas in 1845 empowered white settlers to control the prevailing narrative of the Alamo.

Before the Alamo was a part of the Texans’ history, it was the site of a Spanish mission where colonizers spread Christianity to native populations beginning in 1718. Members of the Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation who converted to Christianity were often buried around or under the mission to remain connected with their new faith. But visitors to the Alamo don’t hear about the Tāp Pīlam people, whose descendants are still seeking protections for the human remains buried under the tourist attraction.

The Alamo took on a new meaning for Prof. Green’s students as they began to wonder how many other stories had been erased from their history textbooks by people in power.